New article!

Pupillary manifolds: uncovering the latent geometrical structures behind phasic changes in pupil size

Phasic changes in pupil size are inherently low-dimensional: three rotated components suffice to reconstruct most changes. Blini et al., 2024

Phasic changes in pupil size are inherently low-dimensional: three rotated components suffice to reconstruct most changes. Blini et al., 2024

Hello there!

A new article is out! Blini et al., 2024

The paper has been covered by a post before when the preprint came out, so I apologize for double posting. I promise, in exchange, new and cool plots! I am actually quite thrilled by this new line of (personal) research and the amazing consequences for future projects as well as practical methodological applications. For example, the package Pupilla has been enriched with amazing functions, which will be presented in the appropriate outlet soon.

For now, I would like to point out a few I believe important theoretical points, not as much the methodological ones. This is not really easy because, arguably, while methodological points are crystal clear, the theoretical ones are more subtle.

The immediate reference is, of course, the concept of Neural Manifolds: latent geometrical structures in a low-dimensional space that encode very efficiently complex information arising, e.g., from population-level neuronal activity. Of course with respect to this kind of signal - neuronal recordings - pupil size is ridiculously low-dimensional by itself: it is one single channel after all. And yet pupillometry has been proven to return a very rich, complex picture of mental processes. Phasic changes in pupil size in particular reflect dynamic shifts between attentional states as instantiated by the locus-coeruleus noradrenaline system, and are crucial for adaptive behaviors according to the extremely influential Adaptive Gain Theory by Aston-Jones and Cohen. What we did thus in the paper is trying to assess the low-dimensional space of these changes across very different tasks: involving responses to light, to cognitive load, or to both. The goal was to see whether, in this latent space, functions could be mapped and separated more clearly.

What we found by using rotated PCA is, quite on the contrary, a common, remarkably similar latent space.

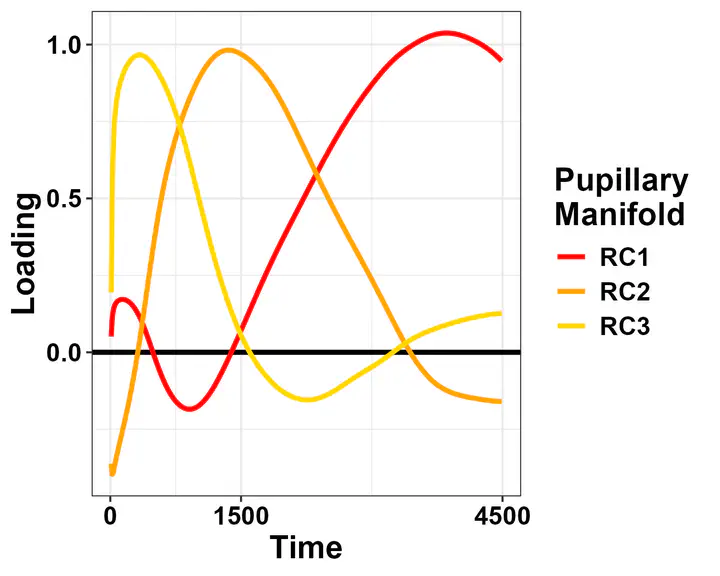

This space is defined by the three loadings depicted above, it has been found by several other authors as well, and is remarkably reminiscent of the different components that constitute autonomic activity (e.g., pupil dilation to cognitive load) as highlighted by pharmacological studies (e.g., Steinhauer and Hakerem, 1992).

The solution really appears task-independent. I find it very likely that it really originates from the “nature” of the signal, and particularly the fact that baseline-correction is used. This implies smaller variability at the beginning of the trial and the largest variability at the end. Thus, it is not really surprising to find that this kind of solution applies everywhere when using PCA or a variation thereof. Still, these shapes do code for latent processes that, altogether, determine the changes in pupil size that are usually taken as evidence for the deployment of a specific cognitive or physiological process. As such, they are much more likely to represent the genuine signal of interest, instead of an ephiphenomenon constituted by several sources. Furthermore, the fact that they more closely resemble distinct physiological processes may bear important consequences for physiological and computational studies, in that providing more neat, physiologically-mindful proxy variables.

Enough talking… I promised cool plots, and here they are!

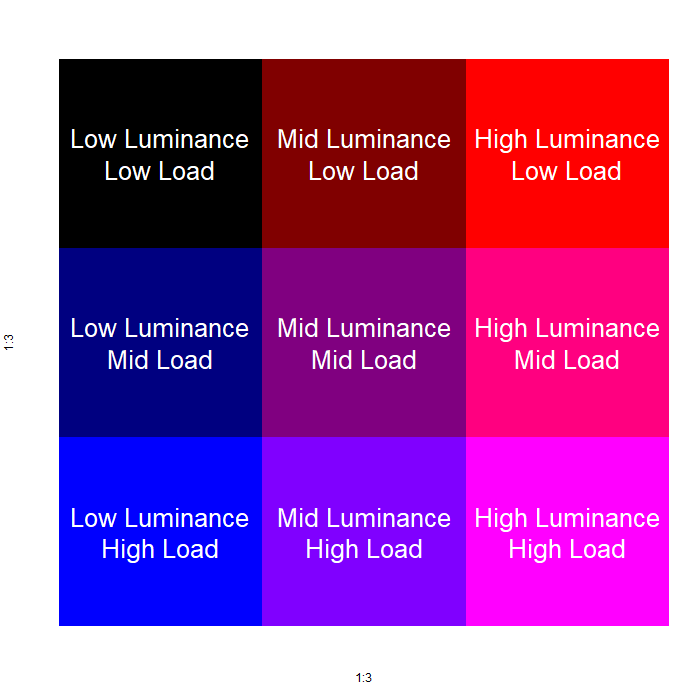

The color scheme:

As you can see, the pupillary manifold can be taken to be sausage-shaped when using this particular PCA variant. This latent structure can code very efficiently for changes occurring along different dimensions: parasymphatetic activation, parasymphatetic inhibition, symphatetic activation; each defined by the corresponding rotated components.

The autonomic balance is a short blanket: these dimensions covary. Effects of light vs cognitive load, so different in terms of both function and neural generators, are indeed coded along the same shape, with little discriminative power from this point of view (i.e., RC3, which defines the “short” side of the manifold). However, there is much interest in attempting to separate, as neatly as we can, these processes, pretty much like heart-rate signals can be decomposed in many different proxy values, which have much more pronounced diagnostic and prognostic value than the original signal itself.

Stay tuned for more about pupillary manifold(s) in the future!

The article can be found at the following link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-78772-x

Abstract

The size of the pupils reflects directly the balance of different branches of the autonomic nervous system. This measure is inexpensive, non-invasive, and has provided invaluable insights on a wide range of mental processes, from attention to emotion and executive functions. Two outstanding limitations of current pupillometry research are the lack of consensus in the analytical approaches, which vary wildly across research groups and disciplines, and the fact that, unlike other neuroimaging techniques, pupillometry lacks the dimensionality to shed light on the different sources of the observed effects. In other words, pupillometry provides an integrated readout of several distinct networks, but it is unclear whether each has a specific fingerprint, stemming from its function or physiological substrate. Here we show that phasic changes in pupil size are inherently low-dimensional, with modes that are highly consistent across behavioral tasks of very different nature, suggesting that these changes occur along pupillary manifolds that are highly constrained by the underlying physiological structures rather than functions. These results provide not only a unified approach to analyze pupillary data, but also the opportunity for physiology and psychology to refer to the same processes by tracing the sources of the reported changes in pupil size in the underlying biology.

Significance statement

Phasic changes in pupil size are thought to reflect dynamic shifts between attentional states as instantiated by the locus-coeruleus noradrenaline system, and are crucial for adaptive behaviors. We found that the latent space of these changes is low-dimensional and remarkably similar across very different tasks, involving distinct cognitive processes. We therefore introduce the notion of pupillary manifolds as latent spaces that subtend the generative processes behind these changes. We suggest that manifolds arise due to hard constraints in the underlying physiological substrate – the relative balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic activity. In the framework outlined here, these mechanisms can be accessed and described directly, with only a handful of parameters, thus better informing computational modelling.